By Mariana Gutierrez Grados, Project Coordinator and communications focal point for Climate Transparency.

If we continue neglecting the impacts of climate change we will exacerbate the inequities and injustices in our society. This year in Bangladesh and India about two million people have been affected by the worst floods in 20 years; the torrential rains submerged cities and agricultural lands and jeopardised people’s security and livelihoods at such risk, forcing one million people to evacuate.

To prevent further temperature increases and slow down the severe impacts of climate change, the energy sector, responsible for three-quarters of global greenhouse gas emissions, must transform toward low-carbon alternatives and leave behind fossil fuels.

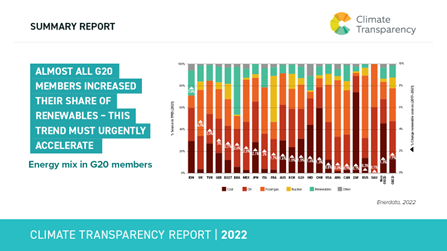

In 2021, the share of renewables increased to 10.5% ,up from 9.1% in 2017 in the G20 energy mix. Still, the energy transition is not occurring at the pace and scale needed to relieve the climate emergency. Fossil fuels account for 81% of the G20 energy mix, and this share should fall to 67% by 2030 and to 33% by 2025 to stay at 1.5°C of warming and prevent further temperature increases. This means that governments must accelerate the energy transition.

To guarantee the sustainability of the energy transition and secure a fairer distribution of its costs and benefits, principles of equity and justice must be central to policymaking. Measures should be implemented at different levels of government and be built on the following pillars (as developed in this analysis):

Parliaments must:

First, place justice, equality, and human rights imperatives as a basis for national and sectoral planning.

Second, build a robust governance structure based on transparency that allows estimating, acknowledging and repairing injustices.

Ministries in charge of implementing the energy and climate agenda must:

Third, implement fiscal, regulatory, and institutional amendments to diversify the economy and provide quality jobs in clean alternatives. Green jobs and training programs need to be in place to address the needs of the workforce affected by the transition.

Fourth, secure climate-resilient spending and allocate budget for the retirement of inefficient fossil fuel projects. Also, the environmental and health impacts caused by fossil fuel projects must be recognized, compensated and fixed, especially for workers, local communities and vulnerable groups. Moreover, governmental incentives and subsidies must promote low-carbon alternatives to enhance local development and protect the environment.

Fifth, establish participatory processes to guarantee the participation of workers, local communities, enterprises, and lower-income households directly affected by the transition and secure free and informed involvement throughout every stage of the energy transition.

Canada and South Africa offer some good examples of progress in this area.

Canada, a founding member of the Powering Past Coal Alliance, is committed to phasing out unabated coal-fired electricity generation by 2030 and has established participatory and engagement processes (pillar 5) involving the actors directly affected by the transition at the local levels.. For instance, the long-awaited Just Transition Act that aims to benefit equity-deserving groups (pillar 1) like women, indigenous peoples, racialised individuals, people with disabilities, and youth has not yet been tabled, even though it started to be discussed in 2019. However, the governance structures are not transforming at the necessary pace to implement phase-out coal plans, and contradictory measures promoting oil and gas must be reversed.

Developing economies could also learn from South Africa, home of one of the most coal-dependent energy sectors in the G20 that has stood out for its efforts to place just energy transition principles as a core (pillar 1) for its national development plans. The Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) is a financing deal between France, Germany, the U.K., the U.S. and the E.U. to support South Africa’s transition to a low-carbon economy and society. Despite being too soon to assess the results of this partnership, having a robust monitoring and evaluation system with transparent and accountable mechanisms (pillar 2) is important to guarantee that the needs of the most affected sectors and communities from the energy transition are attended to in South Africa. Partnerships like this should certainly be replicated in the future with other countries to accelerate the transition.

In previous years, the E.U. had played a leading role concerning just energy transition, for instance, by establishing a Just Transition Mechanism to mobilise EUR 100bn between 2021 and 2027. However, a set of inconsistent government measures that may jeopardise the sustainability of these plans in the mid and long terms can be observed in Germany and Italy due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Since 2020, Germany has provided EUR 40bn until 2038 to support affected regions from phase-out coal plans (pillar 4) and compensate and retrain coal workers. However, in response to the increase in energy prices, coal-fired power plants due to be taken offline in 2022 and 2023 are being reactivated, and the retirement date has been brought forward. Also, in reaction to the ongoing energy crisis, Italy decided to lower fuel taxes and temporarily allow coal plants scheduled for closure to operate at a higher capacity.

Other G20 countries, highly reliant on coal for electricity generation, also worked on advancing decarbonisation.

China, which accounts for half of the global coal consumption and around 50% of global coal power capacity, has significantly reduced employment in the coal sector. Between 2013 and 2021, the coal workforce has halved from 5.3 million to 2.6 million, and renewable energy jobs have doubled from 2.6 to 4.7 million due to the country’s carbon neutrality goal. However, the social and economic impacts must be addressed. For instance, cleaner, affordable energy alternatives must be guaranteed for low-income families and rural households still relying on coal for heating.

Some G20 members have taken backward steps by betting on a greater dependence on fossil fuels, which worsens the climate emergency.

In Mexico, there is a lack of recognition of the social dimension within energy planning and sectoral governance (pillar 1). The current federal administration in Mexico has not yet developed a just energy transition strategy or policy, and programmes to diversify the economy are almost non-existent (pillar 4). The country needs to adopt policies to phase out the use of fossil fuels instead of continuing to promote fossil fuel projects while also reducing the social inequality gap, especially in vulnerable communities.

Russia plans to replace the E.U.’s fossil fuel market with Asia by expanding its export infrastructure to the East. It views the rapid uptake of renewable energy sources across the globe as a threat to its expansion of fossil fuel consumption, production, and exports (pillar 4).

During COP 27, the United States, in collaboration with foundations, announced the “Energy Transition Accelerator”, aiming to scaling-up private finance to developing countries and accelerate fossil fuel phase-out plans. Moreover, the G7 (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, United States and the European Union), along with Norway and Denmark, has announced a 20 billion U.S. dollar partnership to support Indonesia over the next three to five years to transform their energy system.

Despite these and other samples of progress in transforming the global energy systems, doing it faster is key to preventing future temperature rises. Still, the necessary transformations in the years to come can not occur without embedding justice and equity principles into policymaking and international cooperation.