The G7 plays a crucial role in the raising of ambition of climate action this year. The group’s agreements lay the path for the G20 Summit and global climate negotiations at the end of this year. Those seven countries (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States) represent more than 60% of the global net wealth and almost 50% of the global GDP. Therefore, climate policies of these largest economies in the world and their actions are particularly important within the process of transition towards a low-carbon economy.

During the 2018 G7 Summit held on 8 and 9 June in Charlevoix, Canada, the topic of “working together on climate change, oceans and clean energy” will be discussed as one of the 5 key themes of the Canadian presidency.

Ahead of the event it is worth taking a closer look at the climate performance of these seven countries analysed in the Brown to Green Report by the international partnership Climate Transparency.

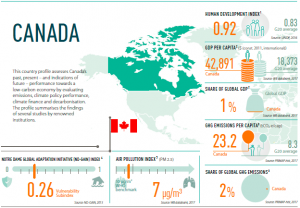

CANADA

Canada performs very low in the two categories of greenhouse gas emissions and energy use per capita – it has the highest greenhouse gas emissions per capita and the highest energy use per capita in the G7. While hydropower dominates its power sector, Canada has one of the highest rate of new wind energy installations.

Experts rate the climate policy performance of Canada’s government medium. They give credit to their government for developing the Pan-Canadian Framework on Climate Change and Clean Growth that sends a signal for a strengthened climate policy.

Although Canada has cut some subsidies to exploration, it continues to subsidise the production and consumption of fossil fuels. In addition, Canadian public finance institutions provided, on average, about US$ 3 billion a year for fossil fuels between 2013 and 2014. While official OECD estimates only report US$ 114 million of subsidies in 2014, other research finds that subsidies to coal, oil and gas production, including through public finance institutions, total US$ 1.6 billion.

Canada’s provision of international climate finance is lower than 0.01% of its GDP, ranking second-last within the G7 countries obliged to provide climate finance under the UNFCCC.

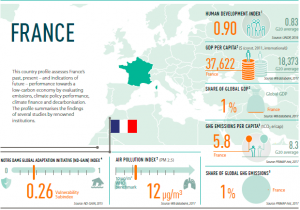

FRANCE

France’s performance in the greenhouse gas emissions per capita category is very high. It has the lowest level of emissions per capita in the G7, with a decreasing trend during recent years. The country performs high in the category energy use per capita.

Experts give France a high score for its policy performance. They expect President Macron to uphold the targets set by the previous administration. France is one of the three G7 countries that has submitted a long-term emissions development strategy to the UNFCCC, and has a national strategy for near-zero energy buildings (as part of EU policies).

France is one of the G7 countries that is highly attractive to renewable energy investment. It aims for a decarbonisation of its electricity sector by 2050, although its renewable energy target remains relatively unambitious. France continues to support fossil fuels, most notably through consumption subsidies for diesel.

France is a frontrunner in green finance: it has the highest market penetration of green bonds within the G7. In early 2017, it issued its first green sovereign bond at EUR 7 billion. France is also the G7’s second largest donor of bilateral climate finance relative to GDP.

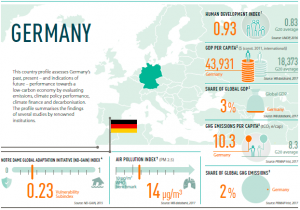

GERMANY

Germany ranks relatively low in the indicator for the level of greenhouse gas emissions per capita due to its high share of coal in energy supply. It has a medium score in the energy use per capita category. Its absolute coal supply has increased in recent years by 11% (2009-2014). It continues to provide significant subsidies to coal and, while it plans to end subsidies to coal production by the end of 2018, it has recently introduced new subsidies for coal-fired power. Germany’s public investment to fossil fuels was, on average, about US$ 3 billion a year between 2013 and 2014.

Experts rate Germany’s policy performance high, but point to the need to improve its sectoral targets and to an adequate phase-out for coal. Germany is one of the three G7 countries that submitted a long-term low-emission development strategy to the UNFCCC and has a national strategy for near zero energy buildings (as part of EU policies).

Investment attractiveness for renewable energy is very high in Germany. It has the G7’s highest effective carbon rate, but this is still too low to meet the Paris Agreement goals. Germany provides the G7’s third largest amount of international climate finance relative to GDP.

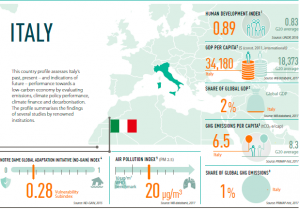

ITALY

Italy’s performance in the categories of greenhouse emissions per capita, and energy use per capita rates very high due to a reduction in emissions and energy use over recent years. Italy’s share of renewable energy (15%) in energy supply is second-large within the G7, followed by Canada (18%).

Italy’s investment attractiveness for renewable energy ranks in the lower mid-range of G7 countries. Having already surpassed its 2020 target for renewable energy, its future pathway is unclear as its 2030 Energy Strategy is still under preparation. There is no strategy on how Italy plans to implement competitive bidding for large-scale renewables as set by the EU. Little new net renewable energy capacity has been installed since 2013.

Following a stable period, the amount of support dedicated to fossil fuel consumption in Italy has also risen sharply since 2012 – to more than US$ 4.6 billion in 2014.

This trend is also reflected in the expert rating of Italy’s climate policy performance: National experts criticise the fact that the focus of energy policy is still mainly on fossil fuels. National and international climate policy continues to be uninspired, and lacks proactivity. Yet, Italy’s performance in hosting the G7 – and prioritising climate protection on the G7 agenda – was seen as a good first step. Italy provides the G20’s lowest levels of international climate finance relative to its GDP.

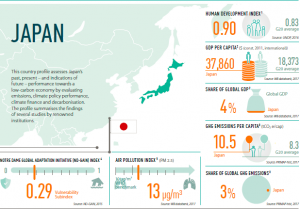

JAPAN

Japan’s performance in the category of greenhouse emissions per capita ranks very low. Its emissions are still relatively high and have shown an increasing trend over the last years. In contrast, it performs high in energy use per capita.

National experts rank Japan’s policy performance very low due to the reactivation of nuclear energy as the main alternative to fossil fuels, instead of sufficiently promoting renewable energy.

Japan has extended its feed-in tariff scheme for wind until 2019, further supporting the strong investments in the technology. Investments in solar energy may be decreasing after the government switched from feed-in tariffs to auctions and a focus on smaller rooftop projects. Japan has two subnational Emission Trading Schemes as well as a national carbon tax – in place since 2012.

Japan provides the G7’s highest amount of international climate finance relative to GDP – most of it as bilateral funding (including efficient coal technologies). However, Japan also spent the highest amount of public finance on fossil fuels in the G20 – an average of US$ 19 billion a year between 2013 and 2014. Moreover, the Japanese government provides subsidies to oil and gas production, mainly to Japanese companies operating overseas.

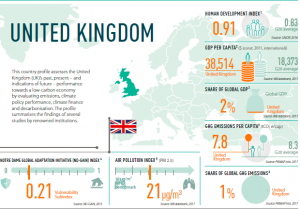

UNITED KINGDOM

The UK performs very high in the categories of greenhouse gas emissions and energy use per capita – both levels have decreased during recent years. The UK has had one of the highest recent growth rates in absolute renewable energy supply, although its share of renewable energy in energy supply remains below G7 average.

Experts rate the UK’s climate policy performance as low. The government has failed to deliver a policy framework for renewables from 2017 onward; the UK Treasury expects investment in renewables to fall by 96% by 2020. The continuation of several other important policies, including zero carbon homes, also seems to be at risk.

The investment attractiveness for renewables in the UK is high. Yet, this is expected to decline due to the recent rollback on policies supporting renewable energy.

By reducing taxes and increasing subsidies to oil and gas production, the UK is the only G7 country that has sharply increased fossil fuel support in recent years. However, the UK claims it has no fossil fuel subsidies, basing that claim on its own definition.

The UK provides the G7’s fourth highest level of international public climate finance relative to GDP, and the highest amount through multilateral climate funds. Between 2013 and 2015, however, it has spent an average of about US$ 6 billion a year of public finance on fossil fuels.

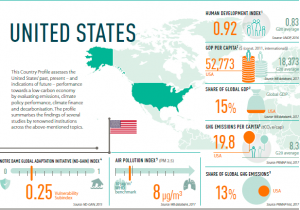

UNITED STATES

The United States performs very low in the category of greenhouse gas emissions and low in the category of energy use per capita. It has the G20’s fourth highest level of greenhouse gas emissions per capita and the highest level of energy use per capita.

After the change in the federal government, national experts have rated both the US’ national and international climate policies down. The US now ranks at the bottom of the G7. If all the Trump administration’s announcements and budget cuts continue being implemented, support schemes for renewables would be reduced. The announced exit from the Paris Agreement is seen as an immense step backwards.

The investment attractiveness for renewable energy in the US is still high, but has been marked by a downward trend. There is uncertainty in the US about possible reductions in the Investment Tax Credit and Production Tax Credit and after the new US administration announced it will review – and repeal – the Clean Power Plan. Such recent developments add to existing federal tax breaks that subsidise various types of offshore oil and gas production.

The US spent an average of US$ 4 billion of public finance a year on fossil fuels between 2013 and 2014. Despite a decline in coal-fired power, federal tax breaks support various types of offshore oil and gas production. Trump also threatens the US’s position as fourth highest provider of international bilateral climate finance and the remaining US$ 2 billion of its Green Climate Fund Pledge.